Indigenous Fighting Villages in the Frontlines of Social and Climate Justice: BALSA Mindanao’s Solidarity Work with the Lumad

By Owen Migraso, Executive Director, BALSA Mindanao:

Editor’s Note: The original version has been shortened for this publication.

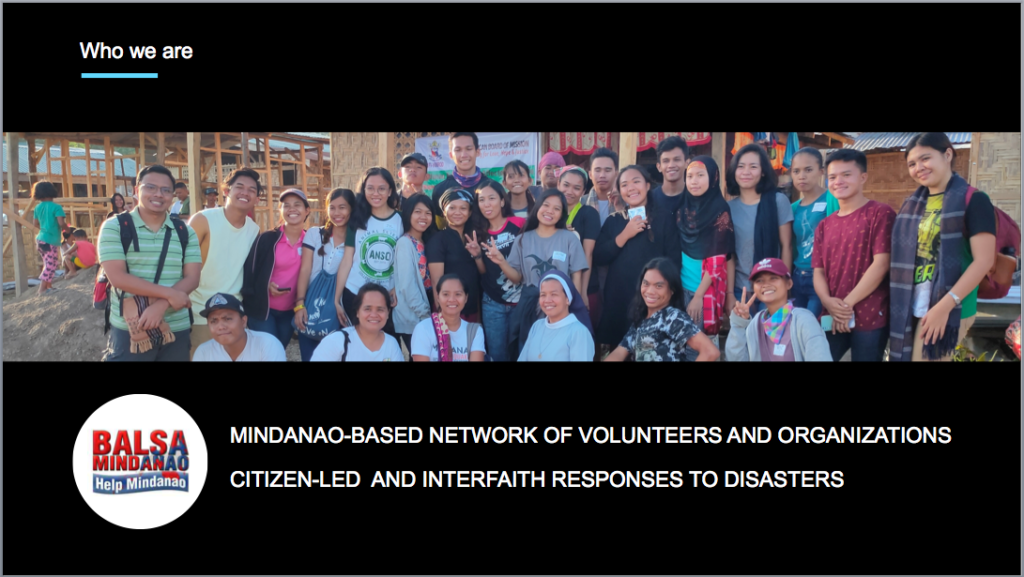

BALSA Mindanao or Bulig Alang sa Mindanao (Help Mindanao) is a network of volunteers and organiza- tions based in the southern island of the Philippines. We do citizen-led responses to disasters, be it natural or man-made. Our responses are interfaith in nature and can take in the form of relief goods delivery, medical missions, psycho-social counselling sessions, and rebuilding work. Aside from this, we also support communi- ties of survivors in their campaigns for social and environmental justice.

We were formed during the aftermath of Typhoon Sendong (Washi) in early 2011. During our first mobilization, we brought in around 150 volunteers from all over Mindanao for our relief and stress debriefing operations. The network also did an information campaign which helped explain that the reason that disaster impacts became amplified is due to the degradation of the Mindanao upstream environment caused by decades of logging, mining, dam building, and large-scale monocrop plantation activities.

We believe that these impacts could have been mitigated, if not avoided, if social protection and sound environmental management policies and programs were put in place a long time ago. We also saw government ineptitude to respond during that time. We had to rely on the local communities and our network of volunteers to effectively deliver our services. That is why we aptly refer to affected communities as disaster ‘survivors,’ as opposed to victims, because we believe in their ability to prepare for the next disaster and, more importantly, advocate for social and climate justice.

When Lumad and Moro disaster survivors push back

Disaster-affected communities today are farming villages which have long experienced the impact of land grabbing of ancestral lands by logging, big mining, mega-dams, and other extractive industries. In the course of their marginalization, many of these communities have stood up as “fighting villages” to defend these ancestral lands “to the last drop of their blood.”

We saw the power of our Lumad and Moro fighting villages and disaster survivors during Typhoon Pablo (2012), Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013), the yearly Manilakbayan, the 2016 El Niño, and the Marawi Siege in 2017. We were in solidarity with the Pablo survivors who organized themselves under Barug Katawhan (People Rise Up). We partnered with a local university and assisted the organization in their reforestation efforts, rebuilding Lumad schools, their homes, and farms. We also saw how 5,000 of these starving survivors stormed the gates of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and took sacks of rice and boxes relief goods that was hoarded from them for several months after the typhoon.

Then came Yolanda (Haiyan) in November 2013. Within 10 days after the near apocalyptic disaster, we had around 25 cargo trucks, buses, and vans with relief goods and 500 volunteers heading to ground zero. We worked in solidarity with the local organization of Haiyan survivors called People Surge in delivering goods for relief and rehabilitation. People Surge campaigned against government negligence and called for national and international support in their fight for climate justice.

We were also in solidarity with the yearly Manilakbayan (Journey to Manila) of the Lumad and other marginalized sectors of Mindanao. Since 2012, they have been marching more than a thousand kilometers from Mindanao to the country capital to bring the southern island’s struggles against human rights violations of the government and environmental plunder of big foreign companies.

During the 2016 leg, Manilakbayan included and highlighted the Moro struggles. It was also at this time that they were joined by other indigenous peoples groups from all over the country and formed the historic Sandugo (One Blood / Blood Compact), a national alliance of national minorities. It aims to heighten their defense of ancestral lands and struggle for self-determination under a unified national movement.

In 2017, our work led us back to our Moro brothers and sisters in Marawi City where from May to October, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) waged an armed siege of the country’s only Islamic City in the name of anti-terrorism. As confirmed in news reports and an Australian government website, the Australian military intervened in the said conflict. They provided two spy planes for surveillance support for Philippine government troops on the ground.

Our partner in Marawi City is the organization of Moro evacuees, Tindeg Ranao, which is still actively campaigning to return to their homes. Thousands of evacuees are still living in tent cities for three long years.

Dangers in the frontlines

Lumad and Moro survivors were met with various forms of harassment and human rights violations. They were vilified, tagged as ‘terrorist,’ filed with harassment suits, illegally arrested, and even summarily killed. Some of our volunteers also fell to these harassments. A leader of Barug Katawhan was also killed days after they stormed the DSWD. People Surge also documented at least 13 killings of their members, 12 illegal arrests, and 6 torture cases by the AFP.

This trend continues up to this day whenever a Lumad, a Moro, a disaster survivor, an activist starts to speak out. Even during these Covid months, the attacks have not stopped.

Last June in Davao City, posters with faces of Lumad supporters were pinned on public places all over the city tagging them as terrorists. A Catholic priest in Surigao del Sur was vilified last May for defending a Lumad school. A Lumad leader in Caraga, also a sister of the only Lumad representative in our current Congress, was illegally arrested last March. Two Moro kids, aged seven and ten, were killed by a mortar that landed on their house in Maguindanao last May.

Despite these conditions, the fighting villages have endured and still continue to organize themselves to seek justice and fight for their rights. The challenge is with us now as a network – how do we continue our solidarity despite the limited mobility? How do we get their stories out there despite the isolation and lockdowns?

Let us continue to support the struggles of the Lumad and Moro of Mindanao!

Leave a Reply